Organizing and Taking Space: Applying Yesterdays Lessons to Todays Culture Wars

By Amilcar Priestley

As the political winds continue to shift nationally, regionally and globally we have dug into the work of past movements to gain some perspective. As an archival repository of the Black Latino movement we did not need to look far.

Starting in the 1960's and continuing into the 1980's, the Black Latin American Social movement experienced a third renaissance, growing rapidly. The work accomplished during this time has become the modern backbone of much of the work around Afrolatinidad you see today. Given the similarities between then and now with a renewed upward fight for civil and human rights, its lessons will serve us well.

Around 1968, Black Latin America's human rights re-awakening exploded. With the memory of Gen. Louvertoure in 1803, Gen. Antonio Maceo in 1896, and many others, our cimarron roots combined with the influences of Garveyites, the Civil Rights struggles of Black Americans and the anti-colonial wave that swept Africa. This re-awakening also came at the heights of U.S. meddling in the region and a rise in U.S. backed military dictatorships. Then, as now, there were detractors within and outside the community. . From the U.S. (Nixon) to Latin America and the Caribbean (Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Dominican, Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Guatemala), organizing communities during this time proved dangerous.

LEARN MORE: https://www.afrolatinofestnyc.com/trending/2020-festival-recap-zine

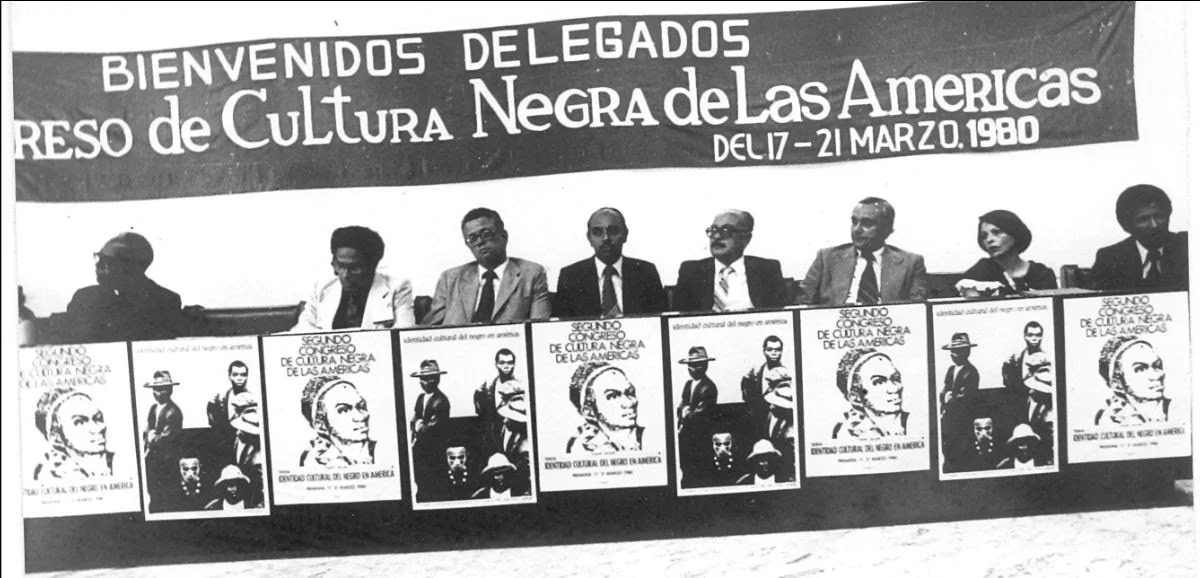

Image: Main Table at the Inaugural Ceremony of the 2nd Congress of Black Culture in the Americas Paraninfo University March 1980 (CEAP/Afrolatin@ Project Archives)

Still, the work accomplished in this era now gives us several important frameworks of action we can adapt to the present day. Here we focus on three:

1) Solidarity and organization building

2) Reaffirmation of cultural expressions, and

3) Documentation and data

1) During this time, several organizations were born, some of which still exist today and some of which have served as the precursor to contemporary Afrolatino organizations. The movement organized locally and regionally with conferences and both open/closed meetings involving academics, artists and organizers. The movement developed an ecosystem. Artists inspired activists, activists inspired artists. And they inspired and were inspired by academics many of whom were first generation.

Takeaway: A reassessment of community engagement is needed. The way we develop community on and offline needs a refresh to inspire action. We need to continue supporting, building, growing and participating in formal organizations and informal collectives alike. Across both, we must build for collaboration identifying areas of common interest that help advance a platform or action, while each also pursuing our particular areas of focus with the support and solidarity of community.

"El fortalecimiento organizacional se entiende como la colaboración, las redes, fraternidad [y sororidad], y unidad con personas y otras corporaciones que permitan el fortalecimiento y crecimiento mutuo de las organizaciones y el movimiento social afrocolombiano bajo los principios de apalancamiento y el panafricanismo.

-CARABANTU.org

Organizational strengthening is understood as collaboration, networking, brotherhood [& sisterhood], and unity with people and other corporations that enable the mutual strengthening and growth of organizations and the Afro-Colombian social movement under the principles of leverage and Pan-Africanism. -CARABANTU.org

2) A key area of organizing focus that proved successful to harnessing the collective and awakening the community was through arts and culture. Fairs, festivals, There was an intentionality to cultural presentations. Cultural affirmation in the face of hegemonic power is important. Recently a cultural battle has been redeclared against Black and Brown people.

Takeaway:

The tools and ideals of old are being imposed. We should look to the tools that first defeated them and refine them for todays realities. Public demonstrations of cultural affirmation is especially important for Afrolatinos. We have only recently begun to reverse the invisibilization we have historically faced. Organizing in person gatherings has nearly always been risky for our communities. We must mitigate risk, but take up space and ensure our voices continue to be heard. Those who can should be mindful to give voice to those who cannot among us. We must also develop a thorough understanding of the state of surveillance we live in, where the lines between the government and private companies get blurrier each day.

3) Documentation of our work; Data collection. During that era, material culture included meeting notes and minutes, posters, flyers, magazines and journals. These publications served to make sure we became visible in popular material culture which historically appropriates without credit or compensation. It also served to inform and inspire those doing similar work in countries facing internal authoritarian or geopolitical pressures. Another important element was the collection of data and documentation of our communities. By the late 1970's several organizations had emerged aimed at ethno-education and ensuring proper Census participation.

Takeaway: Makes it harder to erase us. We are all too familiar with the ways we are invisibilized. Material and written cultural heritage helped tell our stories in mediums from music, dance, visual art and literature. We must document off social media as well as on social. We do not own the popular social media platforms and their owners political leanings continue to change in the wind. As a result, we must not and cannot rely only on these platforms. Saving and backing up your work is important. Similarly while administrations and governments continue to play with data, we must continue to push for ethical data collection and analysis and technology adoption. We must use empirical understandings to complement our traditions and oral histories in order to continue to preserve and advocate for our cultures and lived experiences.

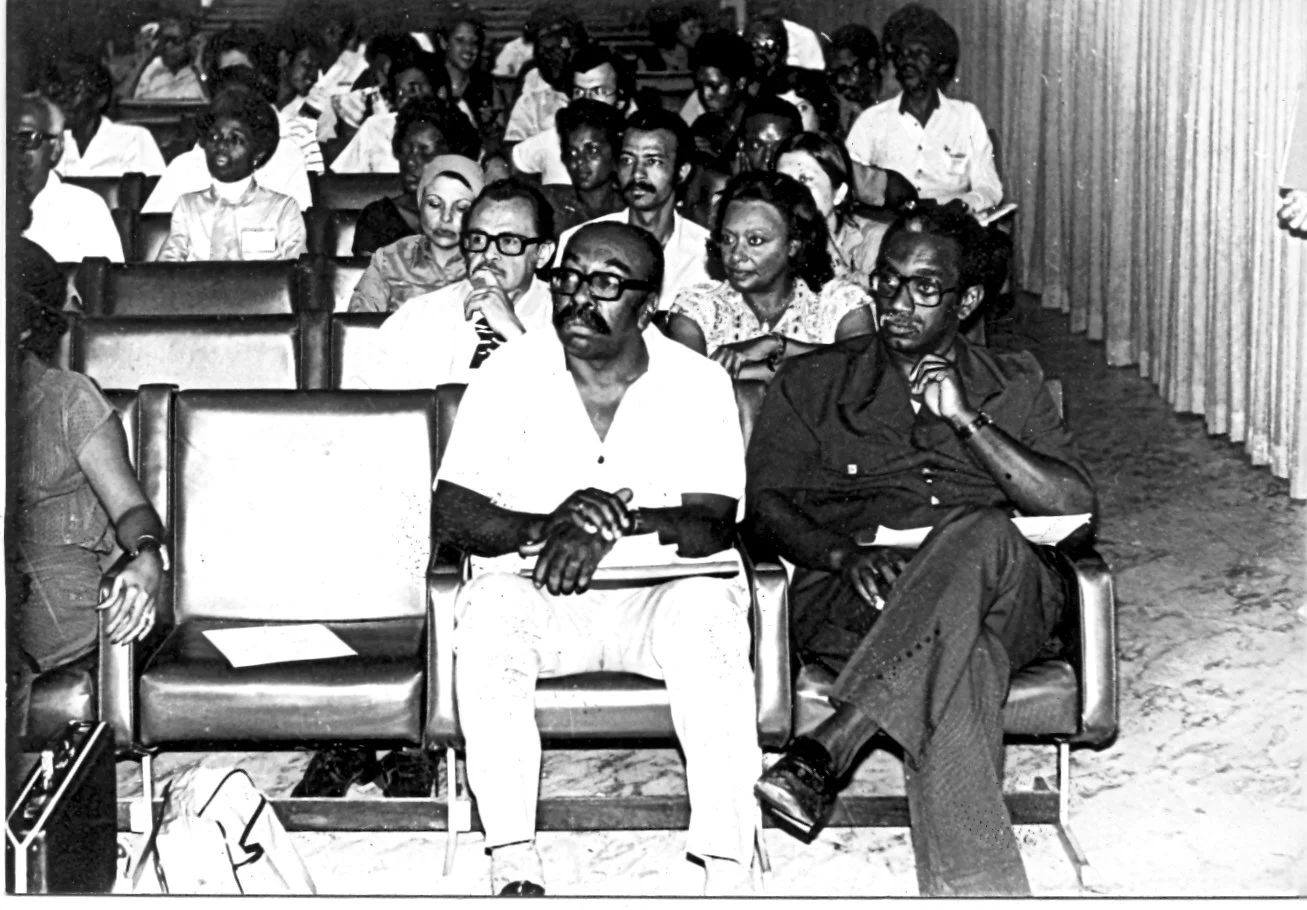

Image: (1, above) Working Group.Dr Roy Simon Brice Laporte , Alberto Smith Fernandez ,Prof Melva de Goodin Panama; (2, below) Nicomedes Santacruz Writer, Peru y Jean Casimir Sociologist, Haiti (CEAP/Afrolaitn@ Project Archives)

Amilcar Priestley

Amilcar Priestley is the Director of the AfroLatin@® Project (http://afrolatinoproject.org/) and co-Director of the Afro-Latino Festival of New York and the Liberacion Film Festival (www.afrolatinofestnyc). Since 2006, Project aims to facilitate the curation of Afrolatino cultures, experiences and histories and to encouraging the use of various tools for the socioeconomic and political development of Afrolatino communities. The Festival is a digital and experiential production platform that educates, affirms and celebrates the many contributions of people of African descent from Latin America and the Caribbean. He began his legal career as an associate at a boutique entertainment law practice and is general counsel at a global advertising agency. He is also the Principal at COI Consulting an intellectual property, licensing and digital media advisory firm. Amilcar is a graduate of Swarthmore College and Brooklyn Law School.