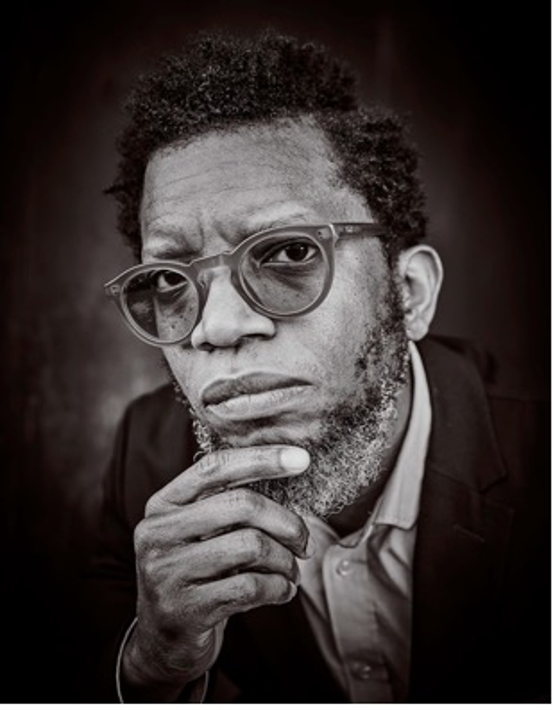

The Creative Mind of Aruán Ortiz

Interview Conducted by Ayanna Legros September 14th, 2025

Ayanna: Tell me a little bit about yourself.

Aruán: Well, my name is Aruán Ortiz and I am a pianist and composer from Cuba. My art flows between tradition and experimentation, composition, and improvisation and highlights Afro diasporic expressions from the Caribbean. I see myself more like a cross-disciplinary artist who integrates stories that resonate with my own life experience.

Ayanna: How old were you when you fell in love with music?

Aruán: I was very little. I don't know when I fell in love with music. There is a constant process of getting deeper into the work, but I started my formal training when I was seven years old.

Ayanna: Was there a specific instrument you were attracted to, or you just explored? Tell me about your process as a kid?

Aruán: I went to a music conservatory when I was a child. I started with violin and at the same time I explored the piano, and both instruments fascinated me! I was really attracted to all the sonic possibilities it provided me. So, when I was around nine years old, I started taking lessons and piano was a complimentary instrument to violin.

Ayanna: And tell me a little bit about your youth. What was your life like with your family? Did you experience things that made you think, okay, this is the direction that is kind of pulling me in?

Aruán: I grew up in a family where music was just entertainment, something you listen to on the radio, or in the dance halls, and not a career. I learned a lot from the conservatory. I had a lot of great teachers. They always, you know, inspired me and motivated me and encouraged me to continue because they saw talent at a very early age. The school curriculum was very strict, you know, and the musical training methodology came in good part from the Russian and Eastern Europe schools, and we had a lot of teachers from there, so the level was really demanding, and the kids were very talented. I absorbed a lot from that environment, and I think I did okay.

Ayanna: A lot of your music, like you already said, draws from the Caribbean, but were there certain nations, islands, and cultures you were curious about and fascinated by? Especially for this album and this current project there are some very explicit Caribbean histories that you explore. I was just curious, you know in your youth, were there other kinds of places that you were dreaming about? Nations that you maybe wanted to travel to or places that inspired you.

Aruán: Oh, I see. I guess being part of the diaspora and living outside of my country for many years made me dive into myself more through reading, researching and composing about the history of the region. I have discovered a lot of fascinating stories and events that portrait the connections between the Afro-Caribbean islands, so I feel that I can extrapolate these tales into my creative process. However, I haven’t really been to any island outside Cuba besides Jamaica. I would like to travel to Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Haiti for sure. When I traveled to Jamaica in the mid-90s, I was in my early twenties. When you leave Cuba, especially for the first time, you think that you are going to a country with new people and new expressions and you think that you are going to see something new… going to Jamaica was new in some sense, and I saw a lot of exciting things, but in terms of people and weather it was the same as Cuba. You see the difference, but I felt like it was as hot or more as in Cuba. You see Black people doing their own thing. It was very interesting. I visited the University of West Indies. I spent some time with the students there. I was amazed by the experience. I would love to go to Martinique. There are stories from people that come directly through that legacy of Afro-diasporic expressions from the Caribbean. For instance, in Martinique there is the legacy of Aimé Cesairé and the Negritude movement. In Haiti there is the legacy of the Haitian Revolution. Where I'm from, there were a lot of connections with Haiti. I have Haitian blood in my family as well. My grandmother’s last name from my father’s side was Barthelemy. This is a last name with Haitian lineage, and I have always been fascinated with this. The first work I did that focused exclusively on the connection between Santiago de Cuba (a city located in the southeast of Cuba) and the Haitian migration was the score for the ballet Santiarican Blues Suite in 2010. I was commissioned by the choreographer José Mateo to recreate a story about the evolution of popular dance from the southeast of Cuba. I had to really research the traditions that impacted and influenced the culture shaped in large part by the huge Haitian immigration from 1801 to 1805 to Santiago de Cuba to write that score. In my research I read some books about it and listened to a lot of musical ensembles that specialized in Cuban–Haitian folklore. Another work of mine dedicated to the Haitian influence onto the Cuban popular music called Changüi, was my trio album Inside Rhythmic Falls (Intakt Records 2020), featuring Andrew Cyrille on drums and Mauricio Herrera on percussion. It also featured my good friend and amazing Haitian singer-songwriter and composer Emeline Michel and Puerto Rican spoken word artist Marlene Ramirez-Cancio, who recited the poem Lucero Mundo, written in three languages: Spanish, English, and Haitian Creole, for the opening track of the album. Changüi, is a very popular musical style from the city of Guantánamo, the most Southeastern part of Cuba, but also from the mountains of that region, because the Haitian community that landed in that part of Cuba established themselves in rural areas. So, during one of my trips I visited some of those communities to learn more in depth about their practices, dances, music, and it was fascinating. Some of these practitioners still speak Kreyòl and French and were able to visit Haiti and interact with to the locals when they were there. I was not aware of that cultural tradition when I was growing up in Cuba. I had no idea. I started learning about that history while living abroad. It’s important, because it made me who I am, and it connected me with that lineage and those traditions.

Ayanna: Right. It's very clear that you love to do research and absorb as much information as possible to propel you forward in your projects. Can you tell me some books or films or music that inspire you specifically, as it relates to Haiti? You mentioned Emeline Michel. Are there other people that you feel are important to connect with artistically in person or through listening or reading?

Aruán: Yeah, I mean, I've been curious to learn about the Haitian revolution, and figures such as Toussaint L’Ouverture, Henri Christophe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Jean-Pierre Boyer, General Alexandre Pétion and the Femmes Rébels. I remember when we spoke about this, and you shared some interesting information about your family lineage that is traced back to that period which made me read more about it. I don't know if you remember that, but I do.

Ayanna: Yes, of course. We went to see The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modern exhibit at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

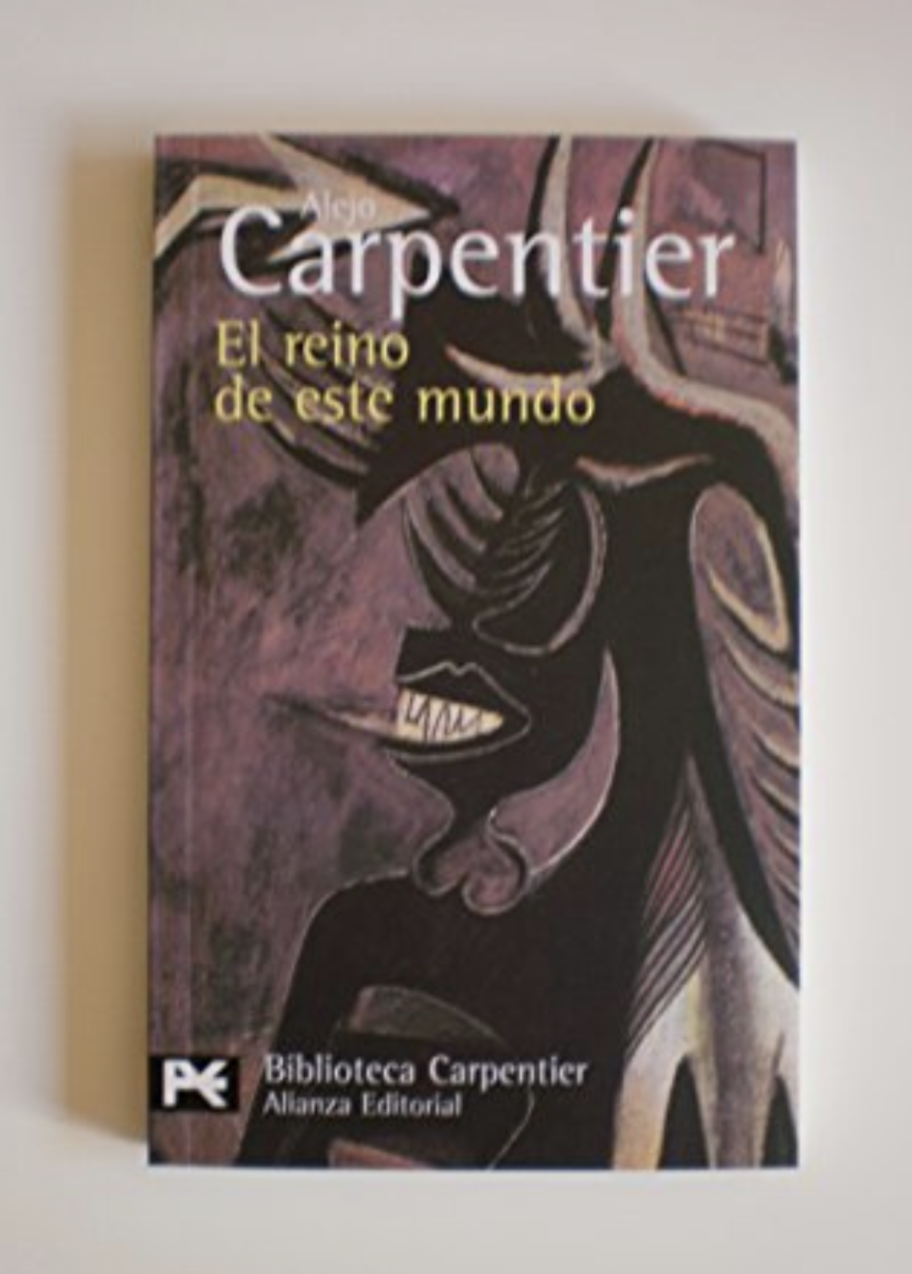

Aruán: That's correct. I re-read Alejo Carpentier’s El Reino de Este Mundo, and I realized that it was inspired by a half magic, half real man named Makandal who was important to stories about the Haitian Revolution. Alejo Carpentier traveled to Haiti with Cuban painter Wifredo Lam in 1944, in an expedition organized by French poet André Breton, the famous Surrealist, and the exiled Haitian writer René Depestre, who was also part of the Surrealist Movement and Negritude Movement. The connection between the Franco-Caribbean and Cuba was so close as it related to the intellectual literary and musical exchange. My music is informed by the traces of Haitian rhythms and history. Of course there is Alix “Tit” Pascal who I met through Andrew Cyrille. I heard about his music and other Caribbean artists that are in the field of creative improvisation, and the way they use their own stories and narratives on their music really expands the listener’s brain. I have been influenced by my own culture and experiences of my hometown so that is what I gravitate towards. Of course, I need to do more research and get deeper into these connections and traces with Haitian traditions.

Reino de este Mundo (Originally published in 1949)

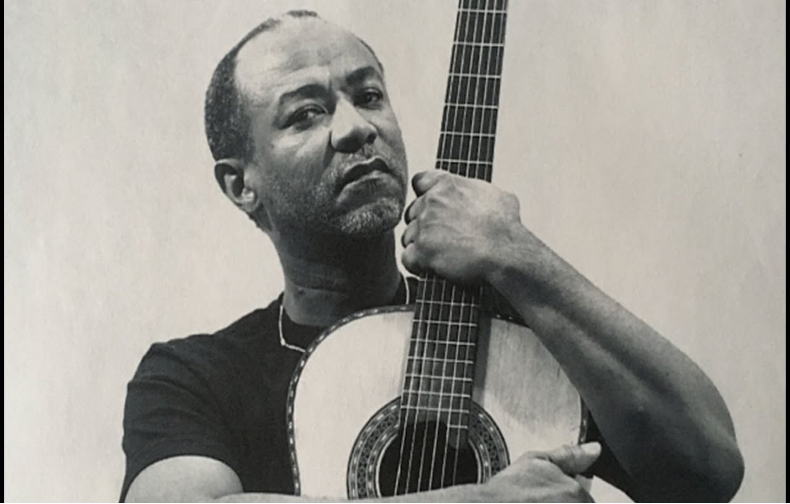

Ayanna: Tell me when, where, and how did you meet Alix “Tit” Pascal?

Aruán: I met him on the same day that I met you. Andrew told me that I needed to meet Alix. I listened to his albums, and realized that one of my mentors and musical references and heroes, the flutist and composer James Newton, did a recording with Alix entitled X Man. It was recorded in 1994. James mentioned his experience performing with Alix Pascal and said that it was fantastic. Alix’s music is very rooted in Haitian culture and the mix between Haitian music and Jazz and improvisation is very amazing.

Ayanna: What do you remember about your grandmother with Haitian roots? Is she alive? Did you get to interact with her? What were your conversations like with her?

Aruán: Well, that is my next research project - that side of my family history.

Ayanna: Yay, okay, you're doing family history! Oh, you just put a huge smile on my face.

Pictured: Andrew Cyrille, Lionel Legros, Jessie Cadet-Legros, a concert attendee, and Alix “Tit” Pascal at Dizzy’s Club - Lincoln Center in New York City, Saturday, June 10th, 2023, at “Caribbean Cross-Generations with Andrew Cyrille, Giventon Gelin, and Shenel Jones” performance. (photograph by Ayanna Legros)

Alix “Tit” Pascal, photographed by Alix DeJean (circa 1980-90s)

Aruán: This was inspired by the research that you shared about your family history, and your relationship with Léonice Legros and Madame Chancy-Louverture. I think my family went to Cuba around the end of the 19th century as sugar cane and coffee laborers. This was considered the second wave of migration from Haiti (the first being in 1800–1805 during the Haitian Revolution). After the huge economic crisis in Cuba in 1929, the government tried to send these immigrants back to Haiti due to the lack of work; however, most of them found refuge in the mountains of southeast Cuba and in other regions. That’s a story I’d like to research more in depth, to find the connection between that period and the history of my paternal family. I already spoke with my brother about this, so we are building that side of my family tree, since we did not have much contact with them.

Portrait of Léonice Legros by Séjour Legros

located in Port-au-Prince at MUPANAH.

Ayanna: You have no idea how much I'm smiling right now. I don't think you understand. If you want I can put you in touch with Association de Généalogie d’Haïti. They do have a list of some last names.

Aruán: Yeah, that could be exciting.

Ayanna: Do you have pictures of your family?

Aruán: Yes, I have pictures of my father. I think that I could get both last names. I know my aunt, my father's sister, is still alive, so she will have pictures.

Map of Santiago de Cuba Map of the Caribbean Sea

Ayanna: You mentioned oral history and I'm thinking, of course, how much of it is a part of the Afro-diasporic experience. So, it's great to hear this. And tell me a little bit about this, I mean, this is such a big question, because obviously I've had to listen to this new album more than once. It's dense, it's deep. You have to really sit, focus, and listen to it carefully. You have a track about Negritude.

Aruán: Oh, yeah, the fourth track.

Ayanna: Can you tell me more about that track? Why is it the fourth one? What inspired you to share the words that you shared? How did you even write and select and cut and edit the things that you shared, and can you formally introduce me to the name of this most recent album?

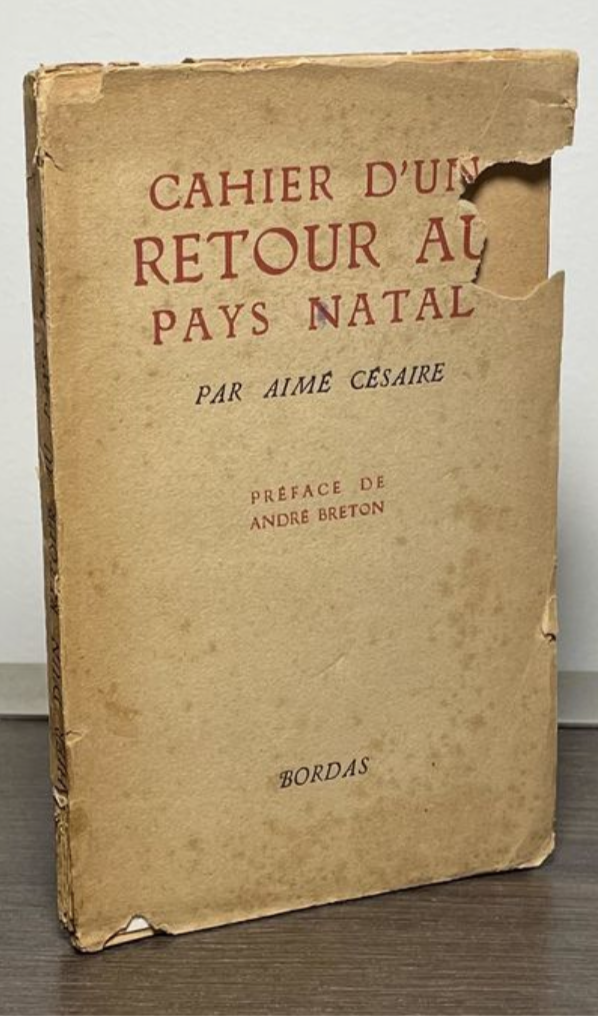

Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Originally published in 1939)

Aruán: Yes. Créole Renaissance is my new solo album released by Intak records on August 29th. Well, track four is a poem. It was inspired by Aimé Cesairé’s Notebook for the Return to my Native Land (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal). That poetry book is a masterpiece, and was written using some surrealistic techniques like anaphora, repetition, expansion, etc. These literary tools inspired me to write the poem From the Distance of my Freedom included on the album. The poem narrates the Afrodiasporic experience intertwined with my own story and living experience as well. It’s not meant to be perceived as a passive reflection, but as a bold statement where the I, subject of that experience, and where the “ism”, are merely rhythmic tools and word devices to build that structure. The music has a lot of contemporary classic musical techniques from the 20th century like serialism and atonalism, so that sonically balances the poem.

Créole Renaissance

Ayanna: Tell me about your upcoming event.

Aruán: This upcoming event is a premiere of the Chamber Opera “Je Renais de mes Cendres,” inspired by the one and only Haitian Queen Marie Louise Christophe. It will be presented in Brooklyn at Roulette Intermedium.

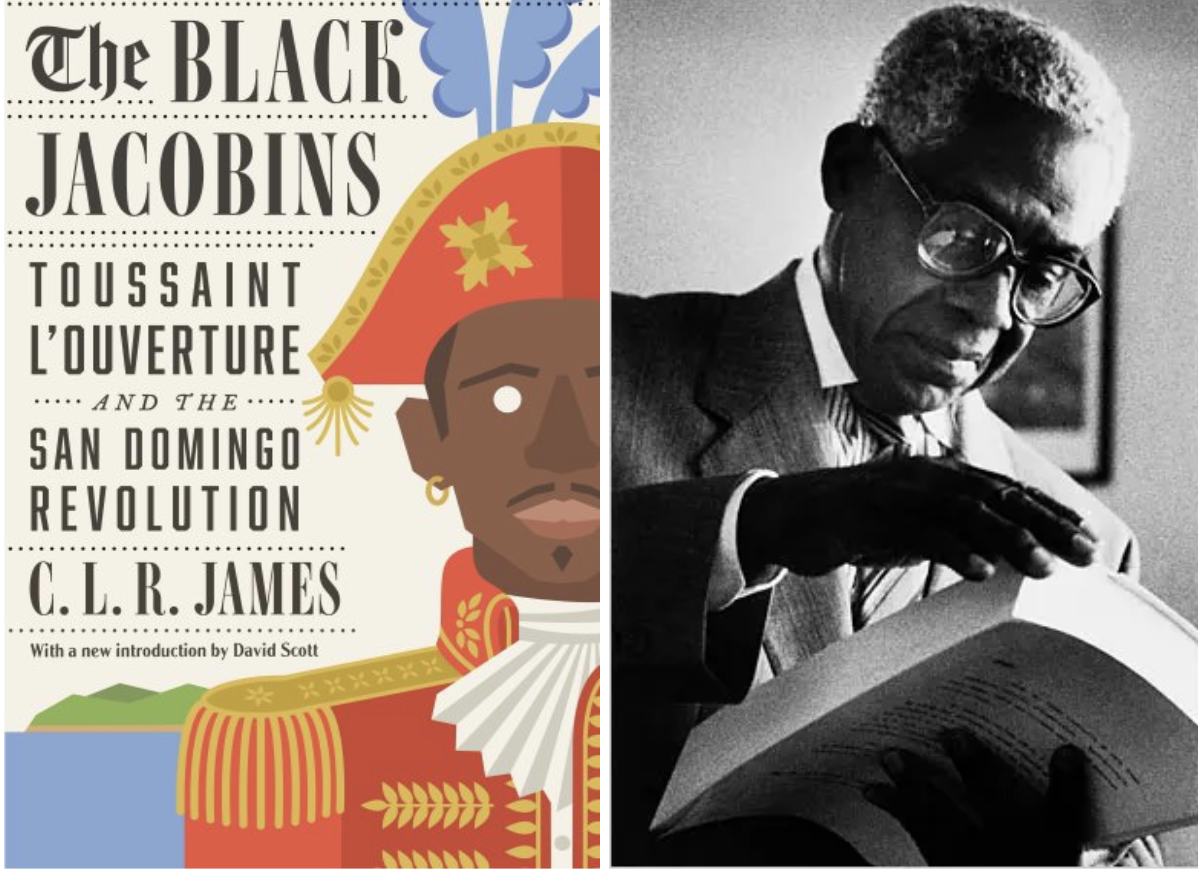

Ayanna: I think you were holding The Black Jacobins when we went to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in the summer.

Aruán: Yeah, The Black Jacobins, that's right. An amazing book about Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution written by the great Trinidadian author C.L.R. James.

Ayanna: Why did you pick that story, by the way? Why Christophe? I mean, you've spoken a lot about Toussaint L’Ouverture, but why Christophe?

Left Image: C.L.R. James’ Black Jacobins Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution

Right Image: Aimé Césaire photographed by Chester Higgins for the New York Times Obituary April 18th, 2008.

Aruán: I thought about how Aimé Cesairé portrayed the figure of Marie Louise in his play, The Tragedy of King Christophe, and I started to think that maybe I could expose a different story with her as the main character, and not as a simple submissive wife. In Césairé’s book, there is a part where he portrayed Marie Louise Christophe, with a lot of servitude, docility and submissiveness. I was curious. I dug into her own story. I learned that Henri and Marie Louise’s relationship was strong since they were young individuals, even before the Revolution. According to some historians, she infused him with the seed of anti-colonialism and anti-French sentiment. She was a very educated, upper middle class, free Black woman, she knew how to read. Her father owned a hostel or a hotel where Christophe was worked when he was a teenager. Some scholars say that she was with Henri Christophe, at the Bois Caïman (Bwa Kayiman) ceremony where revolution officially started. Also, in the middle of the revolution, she was the backbone of the family and Henri’s closed ally. I think her story is extraordinarily fascinating. So, I decided to write a Chamber opera about her. I will present it as just a work in progress for now, since I am still researching and finding historic information about her to complete the libretto. It’s also written in three languages. English, French, and Haitian Creole. Let’s see how it goes. I should publicly thank you for the time you and your mother spent, helping me with the phonetics of the libretto.

Ayanna: I had her play the role of Christophe.

Aruán: That was very nice. They go back and forth in French, Kreyòl, and English. It is a homage to those great warriors that resonate in my culture.

Ayanna: Wonderful. Well, I think this is it. This was more than enough to process and I'm really excited to share this interview with others. I'm super excited to see how everything continues to grow and I'm more than happy to support you. And I love the fact that you make these direct connections between Cuba and Haiti because as you all already know they are so deeply connected. It's great that we can all learn about these histories at once rather than study this nation or that nation in a separate vacuum. It’s not easy to do comparative work. Kudos to you and your willingness to expand your ideas. I just made a work of art about a contemporary woman who is incredibly protective of her husband. She was doing so many things behind the scenes while her husband sat in a detention center. The world knows his name so much more than her name. This process of writing about the women in the lives of these important male historic figures' lives is so important. Continue to do that work. I'm going to start calling you a poet. A poet. Yes. Wouldn't you consider yourself to be a poet?

Aruán: I consider myself a storyteller. The medium I use to express my voice is not relevant. I mean, of course, music is my natural creative vehicle, but I also draw inspiration from other artistic disciplines. I like to compose and improvise and decontextualize forms. I find it as another way to use creative expressions, so, that’s why I found Césaire to be a very fascinating reference. Some words can be translated into rhythms. Léopold Sédar Senghor wrote that a poem “is perfect only when becomes a song: words and music at once”, so when I’m composing, I listen to shapes, the pace, the rhythm, intensity and gestures of a poem, it provides so many ideas, tools, and materials to be used in my composing process. So, thank you, I appreciate that. I didn't see myself as a poet. It's a powerful source for creativity.

Ayanna: Beautiful. That's a wonderful place to conclude. Thank you so much. Congratulations on releasing Créole Renaissance. Gracias Aruán. We will talk more soon.

Aruán: Yes, absolutely. Ciao.

Aruán Ortiz: https://www.Aruán-ortiz.com/ instagram: @elfuriosojazz

Ayanna Legros:https://ayannalegros.com/ Instagram: @haitiharlem

Ayanna Legros is a mixed-media artist, Haitian Studies scholar, and radio preservationist